Research note: Private credit does not pose material financial stability risks, according to regulators & academics

Key research findings

Private credit has lower historical default rates than similar lending options.

Private credit is well equipped to withstand periods of market stress because they are less likely to be forced sellers given investor liquidity limitations.

Private credit financing relationships with banks establishes a better risk allocation, with private credit bearing the first loss.

Private credit funds must report significant data to regulators, undercutting arguments that the industry is opaque.

Private credit, including business development companies (BDCs), have become new sources of corporate lending over the past 15 years, prompting critics to claim these industries have become so big that they could threaten financial stability. But the reality is that many of the concerns raised by policymakers and interest groups are based on mischaracterizations or weak empirical evidence.

There is now a growing consensus among academics and regulators—most recently, from the Federal Reserve’s 2025 stress tests—that private credit does not pose a systemic risk to banks or the broader financial system (Federal Reserve Board of Governors, 2025).

This note examines the research that is correcting the record on private credit.

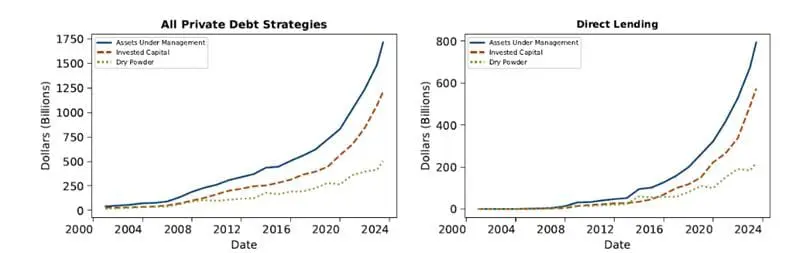

Figure 1: Growth of direct lending

Source: FEDS Note 2025

Private credit funds often impose stricter lending covenants than banks

The loan covenants private credit firms use to protect their investments and monitor borrowers’ financial health are typically stricter than credit originated by banks, which is often broadly syndicated. Unlike syndicated loans, private credit funds hold loans to maturity and bear all of its credit risk, incentivizing them to impose stricter covenants than those imposed by banks.

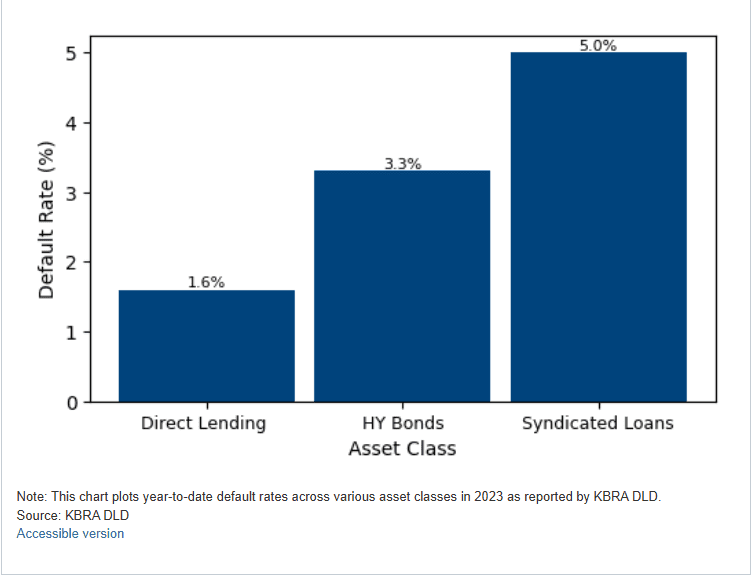

Covenants may include requirements to maintain certain financial ratios or restrictions on additional borrowing, asset sales, or dividend statements. Such conditions have helped private credit achieve lower historical default rates compared with similar lending types.

A February 2024 Fed research note found that private credit direct loans have a default rate of just 1.6%—performing more than twice as well as high-yield bonds (3.3%) and over three times as well as syndicated loans (5%) (Fang and Haque, 2024).

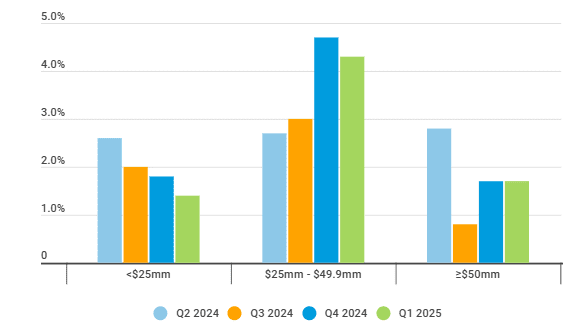

Other research has found similar default rates. Proskauer’s private credit index calculates private credit loan default rates at 2.4% in 2025Q1 (Proskauer Rose, 2025). The index also shows default rates across EBITDA are low (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Year-to-date default rate (As of Oct 2023)

Source: Cai, Fang, and Sharjil Haque (2024).

Figure 3: Default rate by EBITDA

Source: Proskauer

Moreover, research shows that relationships between private equity and private credit lenders do not lead to weaker lending standards. Jang (2024) and Block, Jang, Kaplan, and Schulze (2024) find that direct lenders maintain strong bargaining power and stable underwriting practices, even when working closely with private equity sponsors. Additional analysis by Jang and Rosen (2025) finds no evidence that affiliated lenders offer below-market terms. In fact, as fiduciaries these lenders must only offer arm’s length terms according to SEC regulations. This conclusion is supplemented by Pitchbook, which finds that sponsor-levered deals have become increasingly rare, comprising less than 10% of loans issued by lenders affiliated with private equity funds. For reference, 33% of private credit funds are affiliated with private equity funds (Jang, 2024). Taken together, this evidence shows that private credit lenders tend to impose strict standards on their borrowers and have lower default rates than other lenders.

Private credit distress is typically resolved through market discipline

Evidence from the 2007/09 global financial crisis and COVID-19 shock indicates private credit funds are structurally resilient in periods of market stress, and when they do fail, they do not pose systemic risk. These crises caused valuations to fall across the industry, and some funds became distressed or defaulted on their debts. However, long investor lock-up periods prevented liquidity mismatches, while low leverage and substantial dry powder gave most funds the flexibility to manage through the downturn.

Importantly, failures that did occur were resolved through market discipline, without requiring government intervention (Jang and Rosen, 2025). Distressed funds were either able to recover or were acquired by better-managed competitors. For example, Allied Capital Corporation was acquired by Ares Capital Corporation after the crisis revealed a substantial deterioration in the value of Allied’s loan portfolio (Jang and Rosen, 2025). This evidence reinforces the view that private credit distress can be contained and resolved within the market.

Private credit’s interconnectedness with banks is not a material financial stability risk

Recent research by the Federal Reserve shows that the interconnections between banks and private credit vehicles do not pose a material risk to the banking system (Berrospide, Cai, Lewis-Hayre, and Zikes, 2025).

Although private credit funds tend to use their bank credit more intensively than other nonbank financial intermediaries (NBFIs), the lending is prudently managed. Bank loans to private credit funds have higher interest rates, lower probability of default, and lower delinquency rates compared with those extended to other NBFIs. Loans to private credit funds are also well collateralized, further mitigating the effects of a default on fund investors.

Berrospide et al. also find that, although the private credit market has rapidly grown, it remains small relative to the sizes of other NBFIs. Most bank lending to private credit funds is through revolving credit lines, which are typically drawn only as needed. This structure means that bank exposure is contingent rather than constant, reducing the risk of sudden losses or liquidity pressure. As of the latest data, banks hold about $95 billion in credit exposure to private credit funds and BDCs—$79 billion in revolving credit and $16 billion in term loans—with private credit accounting for just $39 billion of that total. Given the size of the banking system, this is a relatively modest exposure.

Furthermore, the Federal Reserve Board of Governors found in its 2025 Dodd-Frank stress tests that the banking system is well-positioned to weather extreme losses at private credit funds.

One scenario tested banks’ reaction to the largest NBFI borrowers, including private credit funds and BDCs, drawing down their full revolving credit lines. The Fed found that even under these extreme conditions, large banks remained resilient and were well-positioned to absorb losses related to NBFIs. The findings suggest that the risks posed by private credit exposures are manageable with the capital buffers of large banks.

At the same time, private credit funds’ interconnections with banks facilitate risk-sharing within the financial system. One prominent example is the use of significant risk transfer (SRT) transactions, which are well established in Europe and increasingly used in the United States. These transactions encompass a wide range of cash and synthetic securitizations that allow banks to transfer portions of their credit risk to third-party investors, such as private credit funds. By transferring credit exposures through SRTs, banks can manage risk more effectively, optimize capital allocation, and enhance overall financial stability. Private credit funds, in turn, assume those risks in exchange for attractive returns, thereby playing a complementary role in the broader credit ecosystem.

Private credit is subject to reporting requirements that are fit for purpose

Private lenders currently report a substantial amount of information to agencies at the federal and state levels, despite claims that the industry is opaque.

Private lending reporting is broken down into three sources of information:

- Regulatory reporting: State and federal regulators collect data from private credit lenders through a myriad of regulatory filings.

-

- Form PF provides the Securities and Exchange Commission, Commodities Futures Trading Commission, and federal financial regulators with information on private funds’ assets, investment strategies, borrowings, holdings, and performance.

-

- State lending license filings vary by state, but typically require a fund to provide borrower information, loan activity and performance, and its financial statements.

-

- Bank call reports require banks to report detailed information with banking regulators regarding any financing it provides to private lenders.

- Public reporting: Three main disclosures are made publicly available.

-

- BDC and Regulated Investment Company reporting requirements, which include forms 10-K and 10-Q under the 1940 Act, provide information about interest rates, maturity dates, and firm’s distribution of assets.

-

- Insurance companies are required to publicly disclose their investment portfolios, which often include a significant stake in private credit, and investment quality and maturity profiles.

-

- Creditors are required under the Universal Commercial Code (UCC) to file a financing statement, which includes information about the collateral, lender, and borrower.

- Commercial data providers: Three main companies — Debtwire, Pitchbook, and Preqin — provide high-quality data including information on return indices, loan type and spread, and performance. These databases are even used by the Federal Reserve and other federal regulators to study the private credit industry.

The breadth and diversity of existing data sources shows that private credit already provides regulators, investors, and the public with ample information. Rather than layering on new requirements, regulators should ensure that they are making the best use of the data that are already available.

Conclusion

The growth of the private credit industry has drawn increased attention from policymakers and regulators focused on financial stability risks. Key concerns include the industry’s underwriting standards, resilience during market stress, interconnectedness with the banking system, and perceived opacity.

However, this review finds that many of these concerns are unfounded or overstated. Private credit lenders often apply stricter underwriting standards than banks and achieve lower default rates than traditional banks. During past periods of market stress, private credit fund failures were limited and resolved through market discipline, not public intervention. Exposure to the banking system is modest, largely contingent on revolving credit lines, and well within the system’s capacity to absorb losses. And while reporting frameworks are decentralized, they already provide regulators with a broad and useful view of the industry.

Taken together, the evidence does not support the view that private credit poses a material risk to financial stability. In fact, private credit funds play a critical role in the economy by offering companies flexible financing structures, promoting investment and capital formation, and providing investors with diversification benefits.

References

Berrospide, J., Cai, Fang, Lewis-Hayre, S., and Zikes, F. (2025). “Bank Lending to Private Credit: Size, Characteristics, and Financial Stability Implications,” FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, May 23, 2025, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3802.

Block, J., Jang, Y. S., Kaplan, S. N., and Schulze, A. (2024). “A Survey of Private Debt Funds,” Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 13:2, pp. 335–383.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2025). 2025 DFAST stress test results. Retrieved from Federal Reserve website: https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2025-dfast-results-20250627.pdf

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Loans and Leases in Bank Credit, All Commercial Banks [LOANS], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LOANS, July 2, 2025.

Fang, C. and Haque, S. (2024). “Private Credit: Characteristics and Risks,” FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 23, 2024, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3462.

Federal Reserve Board. (2025, April 11). Financial stability report. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/financial-stability-report-20250425.pdf

International Monetary Fund. (2025, April 22). Global financial stability report: Enhancing resilience amid uncertainty. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2025/04/22/global-financial-stability-report-april-2025

Jang, Y. S. (2024): “Are Direct Lenders More Like Banks or Arm’s-Length Investors?” Working Paper. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4529656

Jang, Y. S. and Rosen, S. (2025). Direct lenders and financial stability (Fox School of Business Research Paper). SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4737655

Managed Funds Association. (2024). Private credit data: Readily available and fit for purpose (White paper). Retrieved from MFA website

Proskauer Rose LLP. (2025). Proskauer’s Private Credit Default Index reveals rate of 2.42% for Q1 2025 [Press release]. Retrieved from Proskauer website